Efficiently sorting gigabytes: the Deferred Merge Sort

The problem

One of the biggest challenges in building Superluminal is scalability. No matter how large a capture file is, it shouldn’t affect framerate, memory usage, or lookup times. This constraint shapes almost every aspect of our core data structures. Seemingly simple problems become surprisingly complex once they have to scale. For example, our profiler assumed reasonable thread counts until that fateful day when we received a capture with 80,000 threads that brought the entire system to its knees. Suddenly, every loop over threads became suspect.

One of those problem areas is the global sorting of performance data. Our profiler tracks system events such as sample events and context switches. For each event, we collect metadata like process, thread, and callstack, and then write the event to a file stream. Every event is accompanied by a timestamp.

As it turns out, real-world capture data does not guarantee events to be correctly ordered on timestamp. One of Superluminal’s goals is to be scalable, so the question is: how can we process the event stream in arbitrarily large files in timestamp order without affecting either memory or performance? Can we sort massive capture files (20+ GiB) with minimal memory usage and minimal performance cost?

Are we solving the correct problem?

Before seeing how we globally sort data, a reasonable question to answer first is: why work with unsorted data in the first place? Aren’t we working around a problem that shouldn’t be there in the first place? First and foremost, on most supported operating systems we receive data from the operating itself. The kernel has support for gathering data, and it is delivered in some format that we have to deal with. On Linux, we have more control over implementing our own capturing backend and choosing our data format. The process of building our own capturing backend revealed several subtleties.

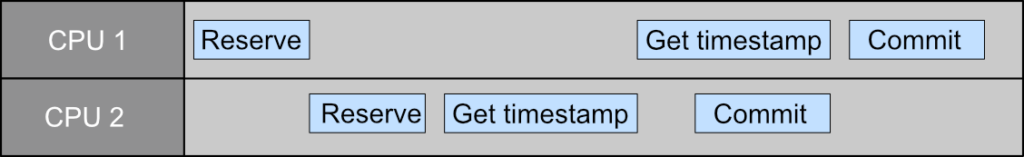

For example, imagine that the kernel is in a context switch and needs to write event data to a shared ringbuffer. We need to get the timestamp and add the data to the ringbuffer. Let’s assume that the ringbuffer is using a reserve/write/commit strategy. If two CPUs are trying to write simultaneously, this is what the timeline could look like:

As the two CPUs are racing for the ringbuffer access, CPU 1 wins this race and reserves first. The head of the ringbuffer is bumped using a lockless atomic operation. Then, the reserve of CPU 2 is performed, bumping the head again. However, CPU 2 retrieves the timestamp before CPU 1 does, and so the timestamp ordering in the ringbuffer is inversed.

This race cannot be solved by fetching the timestamp earlier: it remains a race unless the reserve operation and timestamp retrieval are atomic. So the question becomes: can this problem be reasonably solved?

The first thing to notice here is that we’re already in a callback that fires directly from the kernel’s scheduler. That tells you that we’re in performance critical code. And on Linux specifically, we do this from eBPF, which is a constrained environment where safety and performance are key. We can’t take traditional locks there, and if it would be possible, a lot of concerns would be raised around locking while being in the scheduler’s callback.

Per-CPU buffers avoid the multi-writer race, but they don’t avoid the global ordering problem. Eventually the data from different CPUs must still be merged and sorted. So, for reasons such as this, we would favor performance and safety over a consistent event ordering. It is easier to deal with any out of order issues after the capturing stage.

An analysis

When dealing with such issues, a great start is always to inspect your data. What can we learn from the patterns in our data that we have specifically?

- The majority of our data is already sorted

- When unsorted, values are usually close together

- Wildly out of order values exist, but they are rare

Most of the well-known algorithms are general purpose. We can make something specific to our use case that leverages the fact that our data is mostly sorted. It sounds like we could almost stream our data from beginning to end while dealing with slight out of order issues. What can we learn from tried and tested algorithms?

A well known algorithm is the External Merge Sort, an algorithm that can deal with huge files under fixed memory budgets. Here is quick recap how it works: a first pass splits data into fixed size chunks, and each chunk is sorted individually. Then, a second pass will merge chunks. As the chunks are already sorted internally, we can sequentially read pages of the chunks, and continuously select the lowest value and write it out to a new data stream. The following example illustrates this. Green indicates whether a chunk is loaded into memory.

Even though we’re reading chunks in pages and not in its entirety during the merge pass, there may be an upper bound to how many chunks you can fit into the memory budget at once. If not all chunks can fit into memory, then multiple passes are required to get to the final sorted stream.

Let’s take a modest file size F of 2 GiB as an example and an upper memory bound K of 128 MiB.

A first merge pass will read as many data as it can within memory limits, sort it and write it back to a new file in chunks. In our case that forms F/K new chunks: 2,147,483,648 / 134,217,728 = 16 chunks. If we would perform a 2-way merge, we would merge that down in log2(F/K) additional passes, which equals 4. Each pass performs a full read and a full write, so:

I/O = 2F(1 + log2(F/K)) = 2F(1 + 4) = 10F = 21,474,836,480

However, reading chunks incrementally in pages allows us to consider more chunks and perform N-way merges. The amount of chunks we can have in memory at once depends on our page size. A page size P will allow for N = K/P chunks. For example, if we take an 1 MiB page size, we can read N=128 chunks at once. As we only have 16 chunks in this example, that will easily fit, and the merge becomes a 16-way merge:

I/O = 2F(1 + log16(F/K)) = 2F(2) = 4F = 8,589,934,592

Or, simplified: we then need one sort pass and only one merge pass, so in our example we have 4 times the file size in I/O. These numbers change as the file size F, the memory budget K, or page size P change.

Even at a 16-way merge, this is still a lot of I/O. Can’t we just skip the pre-sort entirely and take the raw stream as-is, and stream it in a single pass?

The algorithm

A key insight is that merge algorithms at least need to know what the initial smallest value of each chunk is. Normally, that requires the first sort pass. But in our case, determining a lowest value for a chunk is almost free. We can split the events into chunks during the capturing process and write these chunks out. We don’t want to sort that data during capturing, but we can just store a minimum timestamp value for a chunk in its header.

Let’s call all these minimum values our per-chunk head, and store them in a head table. This is just a sorted array, and each entry contains a chunk index and head value. In the following example, there are 3 chunks. Each head in the table represents the lowest value in the unsorted chunks (0, 4, 7). The top of the head array shows that chunk 0 is the next to be processed. As chunk 0 is not loaded, we load it, and sort the values inside of it:

Our head starts on event 0, so we process that value. For each value that we process, we update the head in the sorted table. Updating the table is fast: we compare the new head value with the next entry and swap if needed. Because the data is nearly sorted, this typically requires at most a single swap. If it remains smaller than the next item, we know we need to continue in our current chunk. If it is larger, we will continue swapping our entry with the next item in the list until our head is smaller than the next entry.

Let’s consume the values in chunk 0. We push our head to event 0, 1, 3, and when we hit 5, a swap with the neighboring entry occurs in the table:

Entries 0 and 1 have been swapped in the head table. A new chunk is now at the top of the table (chunk 1), so we read it, sort it, and process the first value (4):

After processing element 4, chunk 0 is at the top again, which is already loaded. We process value 5, and as we’ve exhausted all the values in the chunk, we can unload it:

This process is repeated until all chunks and values are processed. Here is the full process of the entire sort:

For our data, at most two chunks are typically loaded at the same time. If a chunk contains values that are far out of order, the algorithm still works: those chunks simply remain in memory longer, until the global output order catches up.

What’s convenient about the sorted table is that it tells us what the next chunk will be that we will need. So during the processing of one chunk, we can prefetch the next chunk and sort it. In our case, we also compress our chunks, so while a chunk is being processed, we read, decompress and sort the upcoming chunk on another thread. This hides I/O, decompression and sorting latency so effectively that global sorting becomes almost free in practise.

Comparison to the k-way lazy merge sort

This algorithm resembles the k-way lazy merge sort ¹. What they have in common is the fact that they are both using a table to store head values for all chunks. Also, chunks are only loaded when needed.

The first difference is that we store our head table in a sorted array. In comparison, the lazy k-way merge sort also stores its heads in a table, but it generally does this using a more sophisticated data structure like a min-heap, a tournament tree, or a loser tree ². The sorted array we use is very simple, and for the input data that we have, very efficient. It is of course less predictable as wildly unsorted values have a worst case of O(N), whereas the mentioned data structures have a more predictable O(log N) complexity. But for our data format, the average mutation will be O(1).

But it’s not the choice of the data structure for the heads table that matters the most. The biggest difference from the k-way lazy merge sort is that that algorithm expects invididual chunks to already be in sorted order. The advantage of chunks already being sorted is that chunks don’t need to be read into memory in their entirety. Instead, chunks can lazily be read in pages smaller than the chunk size. As an example of an extreme case, the k-way lazy merge sort could read chunks in page sizes of 1 event (though that would be inefficient). This approach gives the lazy merge sort the flexibility to be able to evict pages from memory if memory usage gets too high, and then potentially read the page back in again when needed later.

In our case, however, the chunks are explicitly not in sorted order, and we don’t want to have an expensive pre-sort pass either. This means we can’t read chunks in pages, which also means we’re less flexible when it comes to dealing with high memory usage situations: while we could unload a chunk similar to what the lazy merge sort does for pages, on reload we’d have to read the entire chunk in again and sort it again. As a consequence, this would result in pretty big performance overhead if data is not closely sorted.

Future work: A hybrid approach

While the algorithm works efficiently for mostly sorted data, memory usage can spike if values are wildly out of order. To mitigate this, we can detect such values by detecting when a chunk’s head in the sorted table moves back by an unusually large number of positions. We can limit the number of concurrently loaded chunks to a threshold N, unloading any that exceed it. If unloading occurs in such a situation, the already sorted chunk can be written back to disk in a temporary file and we can flag it as presorted. This effectively converts an unsorted chunk into a classical presorted chunk. This is no different then what a first pass would do anyway: load the chunk, sort it, and write it. Think of it as a JIT-sort.

From that point on, the algorithm behaves exactly like a traditional lazy k-way merge for that chunk. If we need the chunk again, we have an already sorted chunk on disk, which means we don’t need to read it in its entirety if we want to. Like a k-way lazy merge sort, we can read values page by page. That way, it would becomes a hybrid approach where we take advantage of closely sorted values, but still support wildly unsorted values without large memory or performance penalties, that will at least perform as well as the k-way lazy merge sort does.

This is demonstrated in the following example. The ‘wildly’ unsorted value is value [3] in chunk 2. After processing the value, the chunk is pushed back in the table. We therefore write it out to a temporary file as a sorted chunk (the peachy color). Subsequent reads from chunk 2 will happen on a page by page basis. For the purpose of this example, the page is just one element, so we read one value at a time from the sorted chunk:

Implementation wise, this would involve some extra bookkeeping in the table, perhaps a flag indicating that we should read from the sorted file, and the cached offset into that file. We can also optimize further by not writing the entire file, but just the remainder that was not processed yet.

This is something we haven’t done as our current setup works efficiently as it is already, but it could be something to look into for the future.

- The k-way lazy merge sort, https://leewc.com/articles/k-way-lazy-merge-sort/

- On min-heaps, tournament and loser trees, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/K-way_merge_algorithm